Draft SEIS outlines alternatives and tools needed to manage drought in the Basin and strengthen water security in the West

From the Department of the Interior:

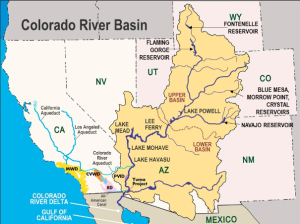

To address the continued potential for low run-off conditions and unprecedented water shortages in the Colorado River Basin, the Department of the Interior’s Bureau of Reclamation (Reclamation) today released a draft Supplemental Environmental Impact Statement (SEIS) to potentially revise the current interim operating guidelines for the near-term operation of Glen Canyon and Hoover Dams. Today’s release comes on the heels of historic investments the Biden-Harris administration announced last week as part of an all-of-government effort to make the Colorado River Basin and all the communities that rely on it more resilient to climate change and the ongoing drought in the West.

The draft SEIS released today analyzes alternatives and measures to address potential shortages in the event that such measures are required to protect Glen Canyon and Hoover Dam operations, system integrity, and public health and safety in 2024 through 2026, after which the current operating guidelines expire. It also ensures Reclamation has the tools to protect continued water deliveries and hydropower production for the 40 million Americans who rely on the Colorado River.

“The Colorado River Basin provides water for more than 40 million Americans. It fuels hydropower resources in eight states, supports agriculture and agricultural communities across the West, and is a crucial resource for 30 Tribal Nations. Failure is not an option,” said Deputy Secretary Tommy Beaudreau. “Recognizing the severity of the worsening drought, the Biden-Harris administration is bringing every tool and every resource to bear through the President’s Investing in America agenda to protect the stability and sustainability of the Colorado River System now and into the future.”

“Drought conditions in the Colorado River Basin have been two decades in the making. To meet this moment, we must continue to work together, through a commitment to protecting the river, leading with science and a shared understanding that unprecedented conditions require new solutions,” said Bureau of Reclamation Commissioner Camille Calimlim Touton. “The draft released today is the product of ongoing engagement with the Basin states and water commissioners, the 30 Basin Tribes, water managers, farmers and irrigators, municipalities and other stakeholders. We look forward to continued work with our partners in this critical moment.”

The SEIS process was initiated in October 2022. The release of the draft follows months of intensive discussions and collaborative work with the Basin states and water commissioners, the 30 Basin Tribes, water managers, farmers and irrigators, municipalities, and other stakeholders. The draft alternatives in the SEIS incorporate concepts from many models and proposals received during the scoping period, including from all seven Basin states.

The alternatives presented in the draft SEIS analyze measures that may be taken under Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland’s authorities to protect system operations in the face of unprecedented hydrologic conditions, while providing equitable water allocations to Lower Basin communities that rely on the Colorado River System.