Deputy Secretary of the Interior Tommy Beaudreau Assistant Secretary for Water and Science Tanya Trujillo U.S. Bureau of Reclamation Commissioner Camille Calimlim Touton

Dear Deputy Secretary Beaudreau, Assistant Secretary Trujillo, and Commissioner Touton: Thank you for your leadership and collaboration as we work together to stabilize the Colorado River Basin amidst an unprecedented, climate change-driven drought stretching over two decades.

Given dire drought conditions across the region and dangerously low reservoir levels, we firmly believe that all water users within the Basin must take immediate voluntary actions to stabilize water supplies in the Basin’s major reservoirs.

California water agencies that utilize Colorado River water supplies propose to conserve up to an additional 400,000 acre-feet of water in Lake Mead each year, beginning in 2023 and running through 2026. This water, which would otherwise be used by California’s communities and farms, will meaningfully contribute to stabilizing the Colorado River reservoir system.

We have identified a collection of proposed water conservation and water use reduction opportunities that would yield approximately 400,000 acre-feet of System Conservation water supplies that could be retained in Lake Mead each year through 2026.

California’s Colorado River water agencies are also prepared to create and store additional quantities of Intentionally Created Surplus water supplies in Lake Mead pursuant to the 2007 Interim Shortage Guidelines, under future favorable hydrologic and water supply conditions. In order to enable this water conservation, our agencies will need to utilize funding opportunities provided by the Inflation Reduction Act and other federal programs.

Each of the California agencies involved in developing this package of proposed conserved water supplies will also require your support in developing agreements for funding, potential intra- and inter- state coordination, water use accounting, and in obtaining necessary board and agency approvals over the coming weeks and months.

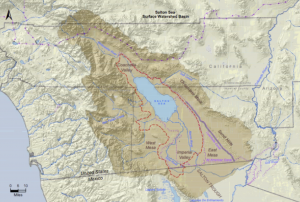

The State of California and its Colorado River agencies appreciate the collaboration of the Department of the Interior and Reclamation to stabilize the Salton Sea, which has been shrinking due to California’s existing water conservation actions and will further shrink when additional conservation actions are taken.

Voluntary water conservation actions outlined in this letter depends on a clear federal commitment to contribute meaningfully to stabilization efforts at the Salton Sea. California has long been a leader in water conservation within the Colorado River Basin, including through the nation’s largest agricultural to urban water conservation and transfer program, the Quantification Settlement Agreement, and through billions of dollars in investments in agricultural and urban water conservation.

In fact, through a variety of activities, California’s water agencies have voluntarily conserved nearly 2.0 million acre-feet of water supplies in Lake Mead since 2007 that has added more than twenty feet to Lake Mead elevations and aided other Lower Basin water users from experiencing previously agreed upon shortage reductions that would have otherwise occurred as early as 2015. Most recently, our water agencies have been committed to constructive participation in discussions among the basin states that began even before to the Commissioner’s call in June for urgent voluntary water conservation. While a broad multi-state agreement to conserve water across the Basin has not been reached, the California agencies propose to take voluntary action now to conserve water in coming months.

It is California’s intention that this proactive voluntary action builds on existing agreements, contracts, compacts, and water rights to catalyze broader basin-wide conservation and helps to avoid protracted litigation that might otherwise result from regulatory or mandated actions. California and its Colorado River agencies believe that it is imperative for the Department of the Interior and Reclamation to immediately reengage the seven Basin States, Tribes, and Mexico in efforts to identify additional water conservation and water use reduction activities to stabilize the Colorado River reservoir system. Additionally, California and the agencies look forward to working with you and others across the Basin with respect to the administrative actions identified in Reclamation’s August 16, 2022, News Release.

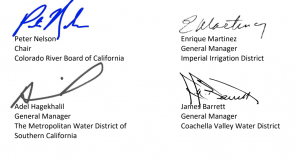

Sincerely,

CC: California Secretary for Natural Resources Wade Crowfoot California Department of Water Resources Director Karla Nemeth Colorado River Basin States Principals