A Desert on the Move

Geologic Hazards and the Future of the Salton Sea

At the Salton Sea, changes in ecology, agriculture, and water rights intersect with human health, geothermal energy production, and geologic hazards. A short distance from the Mexico border, the lake is California’s largest by area, covering 343 square miles. This is changing, however, as the lake shrinks from evaporation and decreasing water input from the Colorado River. Recent changes to regional water use are also driving the rapid shrinking of the lake, leading to ecosystem collapse and increasingly frequent dust storms sourced from the dry lakebed contaminated by agricultural runoff.

This StoryMap will take you back in time to learn about the origins of the Salton Sea and discuss ongoing geologic hazards to the region around the lake. Much of the Storymap is centered around interactive maps that allow the viewer to choose how to explore the Salton Sea and surrounding region. The content of these maps comes from the USGS , Salton Sea Authority , and other organizations that study and manage the Salton Sea; a full list of reference can be found at the end. Note that many of these maps are rotated so that north is to the upper left of the screen. The data used is from publicly available sources noted at the base of each map. Although the sections of this Storymap are meant to be read sequentially; if viewers are interested, the tabs at the top of the screen link to individual sections.

THIS JUST IN … Interior Department Announces Next Steps to Protect the Stability and Sustainability of Colorado River Basin

Draft SEIS outlines alternatives and tools needed to manage drought in the Basin and strengthen water security in the West

From the Department of the Interior:

To address the continued potential for low run-off conditions and unprecedented water shortages in the Colorado River Basin, the Department of the Interior’s Bureau of Reclamation (Reclamation) today released a draft Supplemental Environmental Impact Statement (SEIS) to potentially revise the current interim operating guidelines for the near-term operation of Glen Canyon and Hoover Dams. Today’s release comes on the heels of historic investments the Biden-Harris administration announced last week as part of an all-of-government effort to make the Colorado River Basin and all the communities that rely on it more resilient to climate change and the ongoing drought in the West.

The draft SEIS released today analyzes alternatives and measures to address potential shortages in the event that such measures are required to protect Glen Canyon and Hoover Dam operations, system integrity, and public health and safety in 2024 through 2026, after which the current operating guidelines expire. It also ensures Reclamation has the tools to protect continued water deliveries and hydropower production for the 40 million Americans who rely on the Colorado River.

“The Colorado River Basin provides water for more than 40 million Americans. It fuels hydropower resources in eight states, supports agriculture and agricultural communities across the West, and is a crucial resource for 30 Tribal Nations. Failure is not an option,” said Deputy Secretary Tommy Beaudreau. “Recognizing the severity of the worsening drought, the Biden-Harris administration is bringing every tool and every resource to bear through the President’s Investing in America agenda to protect the stability and sustainability of the Colorado River System now and into the future.”

“Drought conditions in the Colorado River Basin have been two decades in the making. To meet this moment, we must continue to work together, through a commitment to protecting the river, leading with science and a shared understanding that unprecedented conditions require new solutions,” said Bureau of Reclamation Commissioner Camille Calimlim Touton. “The draft released today is the product of ongoing engagement with the Basin states and water commissioners, the 30 Basin Tribes, water managers, farmers and irrigators, municipalities and other stakeholders. We look forward to continued work with our partners in this critical moment.”

The SEIS process was initiated in October 2022. The release of the draft follows months of intensive discussions and collaborative work with the Basin states and water commissioners, the 30 Basin Tribes, water managers, farmers and irrigators, municipalities, and other stakeholders. The draft alternatives in the SEIS incorporate concepts from many models and proposals received during the scoping period, including from all seven Basin states.

The alternatives presented in the draft SEIS analyze measures that may be taken under Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland’s authorities to protect system operations in the face of unprecedented hydrologic conditions, while providing equitable water allocations to Lower Basin communities that rely on the Colorado River System.

The Salton Sea, an Accident of History, Faces a New Water Crisis

Feb. 25, 2023

The vast California lake relies on runoff from cropland to avoid disappearing. But as farmers face water cuts due to drought and an ever drier Colorado River, the Salton Sea stands to lose again.

BRAWLEY, Calif. — The drought crisis on the Colorado River looms large in California’s Imperial Valley, which produces much of the nation’s lettuce, broccoli and other crops, and now faces water cuts. But those cuts will also be bad news for the environmental and ecological disaster unfolding just to the north, at the shallow, shimmering and long-suffering Salton Sea.

“There’s going to be collateral damage everywhere,” said Frank Ruiz, a program director with California Audubon.

To irrigate their fields, the valley’s farmers rely completely on Colorado River water, which arrives by an 80-mile-long canal. And the Salton Sea, the state’s largest lake, relies on water draining from those fields to stay full.

But it’s been shrinking for decades, killing off fish species that attract migratory birds and exposing lake bed that generates dust that is harmful to human health. As the sea has receded, it’s also left abandoned houses, shuttered resorts and landlocked marinas that, in the mid-20th century, had transformed the area into a fishing and water-sports playground for Southern Californians.

Now, with cuts in water use coming after two decades of drought that have left the Colorado’s reservoirs at dangerously low levels, the sea will shrink even faster. “Less water coming to the farmers, less water coming into the Salton Sea,” Mr. Ruiz said. “That’s just the pure math.”

Salton Sea Management Program: Milestone Achieved for the Species Conservation Habitat Project

Earlier this month, the New River started flowing through the New River diversion structure at the Species Conservation Habitat (SCH) project. This signifies an important milestone for the SCH project located at the southern end of the Salton Sea. In the coming months, water from the Sea will also be pumped into the diversion structure to be mixed with New River water and then make its way into the habitat ponds. The network of ponds and wetland aim to enhance environmental values while suppressing dust to reduce potential emissions coming from this area. Construction of the SCH project will continue through 2023 and is on schedule for completion by the end of this year. The 4,100-acre SCH is the first of many projects the Salton Sea Management Program (SSMP) team will implement as part of the SSMP Phase 1: 10-Year Plan. Click here to watch a recent video of the New River Diversion structure that was shared on CNRA’s social media accounts.

Future of the Salton Sea is tied to fate of imperiled Colorado River

A shortage on the Colorado River has put tremendous pressure on the water supply that serves more than 40-million people in the Western United States.

But a punishing drought and the over allocation of the river have also created an urgent problem for California’s Salton Sea.

The 340-square-mile lake was formed in 1905 when a canal carrying river water to farmers in the Imperial Valley ruptured. The flood created a desert oasis that lured tourists and migratory birds to its shore. A century later, the Salton Sea — California’s largest lake — is spiraling into an ecological disaster.

The state of California has started projects to help stabilize the Salton Sea’s shoreline, including this one near Salton City. The hay bales are designed to interrupt the gusting wind and allow natural vegetation to take root. (Peter O’Dowd/Here & Now)

Bombay Beach: A ‘Bohemian community’

At 223 feet below sea level, Bombay Beach occupies a low spot on the map.

Many of the shoreline community’s trailer homes are rusting into the earth and tagged with graffiti. Artists have created large pieces of public sculpture, including a vintage phone booth that stands on the shoreline as a tribute to a bygone era.

During the 1950s and 1960s Bombay Beach was swinging. Celebrities like Frank Sinatra, Bing Crosby and Desi Arnaz flocked to the area.

“People would come here for the boating, the fine dining, the golfing, you name it. For many years, this was the hottest place in Southern California. It was even called the California Riviera,” says Frank Ruiz, Audubon California’s Salton Sea director.

The tourists and celebrities are gone. So are many of the community’s residents. About 230 people live in Bombay Beach now. On a recent windy day, foul-smelling yellow foam collected on the eroding shoreline.

A major drought on the Colorado River is imperling the Salton Sea, California’s largest lake. (Peter O’Dowd/Here & Now)

The Salton Sea’s decline is decades in the making

To understand why the Salton Sea is declining, it helps to look at where the water comes from. The lake is fed almost entirely by agricultural runoff — irrigation water from the Colorado River that drains off nearby farms.

The region is one of the most productive spots for winter produce in the United States. Lettuce, onions, alfalfa, dates and citrus grow prolifically in the mild climate.

In 2003, a deal with the local irrigation district sent a large share of its water to San Diego. That has left less water for local farms — and for the Salton Sea. A hotter and drier climate has also accelerated shortages on the river, which means the lake is shrinking fast.

In certain areas the shore has receded up to 100 feet, Ruiz said. “And with the Colorado River crisis, the Salton Sea is going to recede at a much faster pace,” he added, referring to the federal government’s warning that states must save an additional 2 to 4 million acre feet of water to stabilize the reservoirs and keep the river flowing downstream past Lake Mead.

“This is going to be a nightmare,” he said.

As the water level drops, the ecological disaster grows: The Salton Sea is getting saltier. The birds are leaving. The fish are suffocating.

But according to Ruiz, the real nightmare is what’s lurking in the dried up lake bed: copper, arsenic, selenium and DDT, a toxic insecticide left over from generations of farming.

“When those particles dry up, just think what they can do to the community,” Ruiz says.

When the wind blows, those chemicals get whipped up off the lakebed and become a hazard for the people who live nearby. It’s a problem the state of California is trying urgently to fix.

Senator Padilla Introduces Legislation To Create Salton Sea Conservancy

SACRAMENTO – Senator Steve Padilla (D-San Diego) today introduced Senate Bill 583, creating the Salton Sea Conservancy, unifying the state’s efforts to accomplish necessary and overdue preservation projects, protecting residents’ health, and fostering ecological recovery in the area.

With a surface area of 343 square miles, the Salton Sea is California’s largest lake and was once a freshwater lake and a thriving tourism destination. Evaporation, exacerbated by climate change, along with agricultural runoff, has exposed toxins in the lakebed and created a perfect environment for dangerous algae blooms and bacteria to thrive. Some experts estimate the sea will lose more than half its volume by 2030, creating close to a 3-foot decline in the water level. As the sea shrinks, the lakebed containing elements such as arsenic and selenium becomes exposed, and the dust particles that then become airborne, spread the toxins throughout the region.

The exposure has had an overwhelming impact on the surrounding communities, predominantly composed of Latino agricultural workers. Hospitalization rates for children with asthma in the area are double the state average and residents have been especially affected by the rotten-egg odor from hydrogen sulfide overrunning the sea’s oxygen-deprived water. Imperial County, where the Sea is located, now suffers from some of the worst air quality in the country.

There have been numerous efforts by environmental justice groups to mitigate the negative health effects affecting communities. Similarly, environmental groups have sought aid from state and federal sources to preserve the environment correct the toxic health inequities present. Previous attempts to restore the Salton Sea have stalled despite numerous legislative efforts.

SB 583 would create the Salton Sea Conservancy within the Natural Resources Agency, which would then manage all of the conservation projects taking place in the Salton Sea Region. Conservancies have the ability to foster trust with region they serve. Creating the Salton Sea Conservancy would provide the surrounding community a direct link to a central entity, giving them further insight into restoration efforts.

“This is an environmental crisis that not only impacts the ecology of the region, but the people as well. Communities near the Salton Sea are at breaking point,” said Senator Padilla. “By unifying all of the conservation projects surrounding the Sea, we can streamline .efforts and bring about necessary change faster.”

“We are excited to have a new partner in Senator Padilla, reinforcing our Salton Sea restoration efforts,” said Assemblymember Eduardo Garcia, joint author on the legislation. “A Salton Sea Conservancy creates a necessary avenue to finance operation and maintenance of restoration projects and ensure a healthier, more sustainable future for our sea and surrounding communities.”

“The creation of a conservancy at the Salton Sea to oversee the acquisition and management of land, create infrastructure and act as a responsible steward of wildlife habitat areas is long overdue,” said Frank Ruiz, director of the Salton Sea Program for Audubon California, a member of the Salton Sea Partnership. “As many different entities come together to slow the Sea’s decline, coordination and communication are essential, and we thank Sen. Padilla for working to further that.”

A big rewrite of the water rules?

By Ian James

Debate over Colorado River cutbacks centers on whether evaporation should be counted. Changing the formula would hit California hard. (Rick Bowmer Associated Press)Much of the Colorado River’s water is diverted from reservoirs and transported in canals to the farmlands and cities of the desert Southwest. But some of the water also ends up going elsewhere — vanishing into thin air.

Water lost to evaporation has become a central point of contention in the disagreement between California and six other states over how to divide reductions in water use.

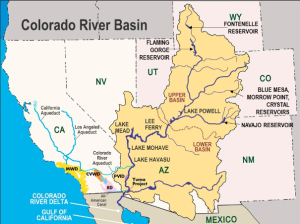

A proposal submitted by Arizona, Colorado, Nevada, New Mexico, Utah and Wyoming calls for relying heavily on counting evaporation and other water losses from reservoirs and along the river in the Lower Basin — the portion of the watershed that begins near the Grand Canyon and stretches to northern Mexico.

Counting those losses would mean immediate reductions of more than 1.5 million acre-feet across the region. It would also translate into especially large water cutbacks for California, which uses the single largest share of the river.

Under the proposal by the six states, Southern California water agencies would be required to absorb the largest share of the cuts, including a potential reduction of more than 18% for the evaporation losses alone, which could rise to 32%if reservoirs hit critically low levels.

The proposal also calls for major reductions in Arizona and Nevada. But the portions of those cuts based on accounting for evaporation would be smaller: about 13% for Arizona and 6% for southern Nevada.

California’s water managers argue that suddenly including evaporation in the math would amount to a drastic rewriting of the rules that would flout the water rights system. They have proposed a different approach that calls for more gradual reductions and wouldn’t involve evaporation losses.

“California’s focus has been, what can we do in the interim that’s pragmatic, practical, doable, that’s not going to make big, lasting changes,” said Wade Crowfoot, California’s natural resources secretary. He said changes that would compromise existing water rights would be “a bridge too far in the near term.”

The Colorado River supplies water to farming areas, cities and tribal nations from the Rocky Mountains to northern Mexico. Chronic overuse combined with 23 years of severe drought and the effects of climate change have pushed the river’s two largest reservoirs, Lake Mead and Lake Powell, to their lowest levels since they were filled.

The growing risk of a collapse in the water supply has prompted federal officials to demand that the states come up with approaches for preventing reservoirs from bottoming out.

Op-ed: Why California controls the fate of the Colorado River

Opinion column by Joe Mathews:

Why do we still call it the Colorado?

Sure, the river begins in the Colorado Rockies. But in law and practice, the waterway making headlines is clearly the California River. And the first provision of any deal to save the river should rename it accordingly.

This condition wouldn’t be about Golden State pride. Instead, a name change would more accurately reflect the imperial role California plays in the movement of water, people, and power in the American West.

Right now, the Grand Canyon-sized divide over how to reduce the amount of water drawn from the rapidly diminishing river is being portrayed as a dispute between states. On one side, six states that rely on California-nee-Colorado water — Arizona, Colorado, Nevada, New Mexico, Utah, and Wyoming — have come together to demand cuts in water use that would fall heaviest on California.

In response, California water officials have produced a plan emphasizing how our state’s rights to the water are more senior than those of our Southwest neighbors. Their newly released plan would cut less from California’s take, and more from Arizona and Nevada. In the Wild West of Water, this argument — We stole it first! We stole it fair and square! — is a strong legal position.

But such descriptions of the fight fail to capture the true dynamics of the situation — that California is less a state than an empire, and the six states challenging it over water are California colonies. California is by far the richest and most dynamic area in this half of North America. California has more residents and a bigger economy than all the other western states of the U.S. put together.

In recent generations, California, like other great empires through history, has grown so much that it has exported people, money, and culture to nearby territories. California’s investment has helped make the intermountain West the nation’s fastest-growing region

Many of the greater West residents are native Californians, or immigrants who came through the Golden State. Nevada is the most Californian state; with nearly as many California natives (20%) as Nevada natives (25%), and more than 90% of its population living within 50 miles of the California border. But Californians have also provided sizable percentages of new residents to Utah, Colorado, and Arizona, where one out of every 10 residents was born here.

Moving to the colonies is so common that the Orange County Register business columnist Jonathan Lansner often builds spreadsheets for his readers examining which of these colonies are doing best. (His latest advice? “Move to Colorado.”)

Are these transplanted Californians, and other residents of the California colonies, grateful for our largesse? Of course not. Colonists don’t freely thank their emperors, which is why every so often, the LA Times or New York Times interviews some real estate agent in Phoenix or Las Vegas or Denver, who whines about how the California ex-pats are driving up housing prices.

Despite separate plans for Colorado River cuts, stakeholders continue to talk

One proposal would bring cuts of 2 million acre-feet of water for users pulling from the drought-choked Colorado River system, mostly affecting California, Nevada and Arizona, in an attempt to conserve the region’s most valuable commodity: water.

When looking at the plan released Monday by six of the seven states that rely on the Colorado River for their water supplies — and fiercely try to protect what they believe is their fair share — one water expert came to a harsh conclusion.

“It’s a bandage for a gunshot wound,” said Kyle Roerink, the executive director at the Great Basin Water Network.

The proposal, Roerink says, falls short because it puts the burden mostly on the three southwestern states — the so-called Lower Basin states.

“I think any time we see a proposal put forth that is going to limit consumptive uses, that’s helpful,” Roerink said. “It’s promising, but when you look at who’s giving up what, it just begs the question: Why does the Upper Basin get off scot-free?”

The Colorado River and its tributaries pass through seven states and into Mexico, serving 40 million people and a $5 billion-a-year agricultural industry. Some of the largest cities in the country, including Los Angeles, Phoenix, Denver and Las Vegas, two Mexican states, Native American tribes and others depend on the river that’s been severely stressed by drought, demand and overuse.

The 1,450-mile river also generates hydroelectric power for regional markets and irrigates nearly 6 million acres of farmland.

States missed a mid-August deadline to heed the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation’s call to propose ways to conserve 2 million to 4 million acre-feet of water. They regrouped to reach consensus last week to fold into a larger proposal the Bureau of Reclamation has in the works.

California bucks a united front as region grapples with Colorado River water cuts

After a key deadline passed this week without an agreement on how to address the Colorado River’s crisis, California is now sharply at odds with six other states over how to take less water from the shrinking river.

Now that California has rejected a plan offered by the rest of the region, the state has entered a political tug-of-war with high stakes. So why has the state that uses the most Colorado River water decided to go it alone?

California appears to be banking on its high-priority senior water rights, while the other states are presenting a united front to show the federal government they support a plan that would have California give up more water.

“The strongest thing that the other basin states have going for them is some relative level of consensus. And the strongest thing California has going for it is the law,” said Rhett Larson, a professor of water law at Arizona State University.

“I think they’re playing to their strengths,” Larson said. “California is trying to play its best card, which is, ‘The law is on our side.’ And the other six states are trying to play their best card: ‘We are on each other’s side.’”

The parties are at an impasse as the federal government begins to weigh alternatives for rapidly reducing water use and preventing the river’s reservoirs from reaching dangerously low levels.

California Water Agencies Submit Colorado River Modeling Framework to Bureau of Reclamation

Proposal Outlines Constructive Approach to Achieve Necessary Water Use Reductions through 2026 to Protect Critical Infrastructure, Prioritize Public Health and Safety

California water agencies that rely on the Colorado River today proposed a modeling framework for the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation to evaluate as it considers actions to help stabilize reservoir elevations and protect critical infrastructure to ensure the Colorado River system can continue to support 40 million people, nearly 6 million acres of agriculture, and Tribes across seven states and portions of Mexico.

The modeling framework outlines a constructive approach to achieve additional water use reductions while protecting infrastructure, prioritizing public health and safety, and upholding the existing body of laws, compacts, decrees, and agreements that govern Colorado River operations (known collectively as the Law of the River). The approach builds on the California agencies’ commitments announced last fall to voluntarily conserve an additional 400,000 acre-feet of water each year through 2026 to protect storage in Lake Mead and help stabilize the Colorado River reservoir system.

California’s proposed framework seeks to protect Lake Mead elevation of 1,000 feet and Lake Powell elevation of 3,500 feet by modifying some parameters governing reservoir operations, maximizing the impact of existing plans and voluntary conservation actions, and increasing cutbacks if Lake Mead elevations decline. It also protects baseline water needs of communities across the West by prioritizing water supplies for human health and safety. The proposal was carefully developed to enable workable phased water use reductions and ensures protection of adequate water volumes in Lake Mead and Lake Powell.

“The alternative provides a realistic and implementable framework to address reduced inflows and declining reservoir elevations by building on voluntary agreements and past collaborative efforts in order to minimize implementation delays. California’s alternative protects critical elevations and uses adaptive management to protect critical reservoir elevations through the interim period,”

JB Hamby, chair of Colorado River Board of California and California’s Colorado River Commissioner, wrote in a transmittal letter to Reclamation.

The approach differs from a modeling proposal submitted to Reclamation on January 30 by the six other basin states. The six-state proposal would direct the majority of water use reductions needed in the Lower Basin to California water users through a new apportionment method based on “system and evaporative losses.” The proposal directly conflicts with the existing Law of the River and the current water rights system and mandates cutback without providing tools to manage reductions.

For the past several months, California water users have sought a timely, practical and implementable solution with other Lower Basin users that can be implemented over the next three years to protect critical elevations in Lake Mead while longer-term changes are negotiated to update 2007 Interim Guidelines that will expire at the end of 2026. Suggestions to fundamentally change the Law of River are appropriately addressed through this shared process to update the guidelines.

California’s water agencies remain committed to working with all Colorado River basin states to take urgent, fair, and achievable action now to avoid unacceptable risks to communities, farms and economies in California and the rest of the basin.

For decades, California has been a leader in managing its Colorado River water resources and collaborating in basin-wide efforts to more effectively operate and manage the reservoir system and to incentivize water conservation as demands have increased in the face of shrinking supplies due to climate change.